this post was submitted on 27 Jun 2024

796 points (95.1% liked)

Science Memes

11440 readers

247 users here now

Welcome to c/science_memes @ Mander.xyz!

A place for majestic STEMLORD peacocking, as well as memes about the realities of working in a lab.

Rules

- Don't throw mud. Behave like an intellectual and remember the human.

- Keep it rooted (on topic).

- No spam.

- Infographics welcome, get schooled.

This is a science community. We use the Dawkins definition of meme.

Research Committee

Other Mander Communities

Science and Research

Biology and Life Sciences

- !abiogenesis@mander.xyz

- !animal-behavior@mander.xyz

- !anthropology@mander.xyz

- !arachnology@mander.xyz

- !balconygardening@slrpnk.net

- !biodiversity@mander.xyz

- !biology@mander.xyz

- !biophysics@mander.xyz

- !botany@mander.xyz

- !ecology@mander.xyz

- !entomology@mander.xyz

- !fermentation@mander.xyz

- !herpetology@mander.xyz

- !houseplants@mander.xyz

- !medicine@mander.xyz

- !microscopy@mander.xyz

- !mycology@mander.xyz

- !nudibranchs@mander.xyz

- !nutrition@mander.xyz

- !palaeoecology@mander.xyz

- !palaeontology@mander.xyz

- !photosynthesis@mander.xyz

- !plantid@mander.xyz

- !plants@mander.xyz

- !reptiles and amphibians@mander.xyz

Physical Sciences

- !astronomy@mander.xyz

- !chemistry@mander.xyz

- !earthscience@mander.xyz

- !geography@mander.xyz

- !geospatial@mander.xyz

- !nuclear@mander.xyz

- !physics@mander.xyz

- !quantum-computing@mander.xyz

- !spectroscopy@mander.xyz

Humanities and Social Sciences

Practical and Applied Sciences

- !exercise-and sports-science@mander.xyz

- !gardening@mander.xyz

- !self sufficiency@mander.xyz

- !soilscience@slrpnk.net

- !terrariums@mander.xyz

- !timelapse@mander.xyz

Memes

Miscellaneous

founded 2 years ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

x=.9999...

10x=9.9999...

Subtract x from both sides

9x=9

x=1

There it is, folks.

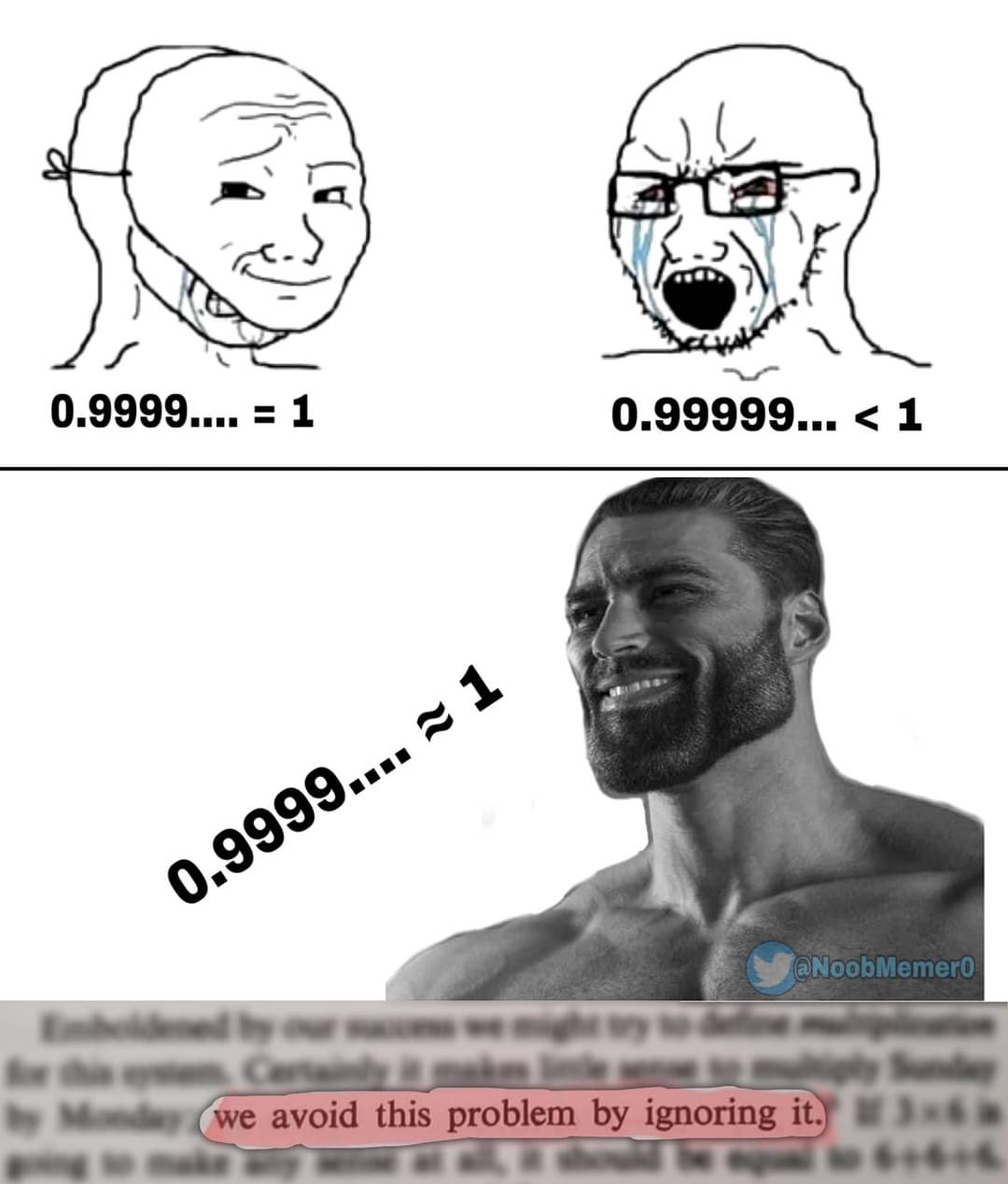

Somehow I have the feeling that this is not going to convince people who think that 0.9999... /= 1, but only make them madder.

Personally I like to point to the difference, or rather non-difference, between 0.333... and ⅓, then ask them what multiplying each by 3 is.

The thing is 0.333... And 1/3 represent the same thing. Base 10 struggles to represent the thirds in decimal form. You get other decimal issues like this in other base formats too

(I think, if I remember correctly. Lol)

Oh shit, don't think I saw that before. That makes it intuitive as hell.

Cut a banana into thirds and you lose material from cutting it hence .9999

That’s not how fractions and math work though.

I'd just say that not all fractions can be broken down into a proper decimal for a whole number, just like pie never actually ends. We just stop and say it's close enough to not be important. Need to know about a circle on your whiteboard? 3.14 is accurate enough. Need the entire observable universe measured to within a single atoms worth of accuracy? It only takes 39 digits after the 3.

pi isn't even a fraction. like, it's actually an important thing that it isn't

pi=c/d

it's a fraction, just not with integers, so it's not rational, so it's not a fraction.

The problem is, that's exactly what the ... is for. It is a little weird to our heads, granted, but it does allow the conversion. 0.33 is not the same thing as 0.333... The first is close to one third. The second one is one third. It's how we express things as a decimal that don't cleanly map to base ten. It may look funky, but it works.

Pi isn't a fraction (in the sense of a rational fraction, an algebraic fraction where the numerator and denominator are both polynomials, like a ratio of 2 integers) – it's an irrational number, i.e. a number with no fractional form; as opposed to rational numbers, which are defined as being able to be expressed as a fraction. Furthermore, π is a transcendental number, meaning it's never a solution to

f(x) = 0, wheref(x)is a non-zero finite-degree polynomial expression with rational coefficients. That's like, literally part of the definition. They cannot be compared to rational numbers like fractions.Every rational number (and therefore every fraction) can be expressed using either repeating decimals or terminating decimals. Contrastly, irrational numbers only have decimal expansions which are both non-repeating and non-terminating.

Since

|r|<1 → ∑[n=1, ∞] arⁿ = ar/(1-r), and0.999...is equivalent to that sum witha = 9andr = 1/10(visually,0.999... = 9(0.1) + 9(0.01) + 9(0.001) + ...), it's easy to see after plugging in,0.999... = ∑[n=1, ∞] 9(1/10)ⁿ = 9(1/10) / (1 - 1/10) = 0.9/0.9 = 1). This was a proof present in Euler's Elements of Algebra.There are a lot of concepts in mathematics which do not have good real world analogues.

i, the _imaginary number_for figuring out roots, as one example.

I am fairly certain you cannot actually do the mathematics to predict or approximate the size of an atom or subatomic particle without using complex algebra involving i.

It's been a while since I watched the entire series Leonard Susskind has up on youtube explaining the basics of the actual math for quantum mechanics, but yeah I am fairly sure it involves complex numbers.

i has nice real world analogues in the form of rotations by pi/2 about the origin (though this depends a little bit on what you mean by "real world analogue").

Since i=exp(ipi/2), if you take any complex number z and write it in polar form z=rexp(it), then multiplication by i yields a rotation of z by pi/2 about the origin because zi=rexp(it)exp(ipi/2)=rexp(i(t+pi/2)) by using rules of exponents for complex numbers.

More generally since any pair of complex numbers z, w can be written in polar form z=rexp(it), w=uexp(iv) we have wz=(ru)exp(i(t+v)). This shows multiplication of a complex number z by any other complex number w can be thought of in terms of rotating z by the angle that w makes with the x axis (i.e. the angle v) and then scaling the resulting number by the magnitude of w (i.e. the number u)

Alternatively you can get similar conclusions by Demoivre's theorem if you do not like complex exponentials.

I want to go to there.

I was taught that if 0.9999... didn't equal 1 there would have to be a number that exists between the two. Since there isn't, then 0.9999...=1

Not even a number between, but there is no distance between the two. There is no value X for 1-x = 0.9~

We can't notate 0.0~ ....01 in any way.

Divide 1 by 3: 1÷3=0.3333...

Multiply the result by 3 reverting the operation: 0.3333... x 3 = 0.9999.... or just 1

0.9999... = 1

You're just rounding up an irrational number. You have a non terminating, non repeating number, that will go on forever, because it can never actually get up to its whole value.

1/3 is a rational number, because it can be depicted by a ratio of two integers. You clearly don't know what you're talking about, you're getting basic algebra level facts wrong. Maybe take a hint and read some real math instead of relying on your bad intuition.

1/3 is rational.

.3333....... is not. You can't treat fractions the same as our base 10 number system. They don't all have direct conversions. Hence, why you can have a perfect fraction of a third, but not a perfect 1/3 written out in base 10.

0.333... exactly equals 1/3 in base 10. What you are saying is factually incorrect and literally nonsense. You learn this in high school level math classes. Link literally any source that supports your position.

.333... is rational.

at least we finally found your problem: you don't know what rational and irrational mean. the clue is in the name.

TBH the name is a bit misleading. Same for "real" numbers. And oh so much more so for "normal numbers".

not really. i get it because we use rational to mean logical, but that's not what it means here. yeah, real and normal are stupid names but rational numbers are numbers that can be represented as a ratio of two numbers. i think it's pretty good.

I know all of that, but it's still misleading. It's not a dumb name by any means, but it still causes confusion often (as evidenced by many comments here)

fair enough, but i think the confusion for that commenter comes from a misunderstanding of the definition of the mathematical concept rather than the meaning of the English word. they just think irrational numbers are those that have infinite decimal digits, which is not the definition.

it's literally repeating

In this context, yes, because of the cancellation on the fractions when you recover.

1/3 x 3 = 1

I would say without the context, there is an infinitesimal difference. The approximation solution above essentially ignores the problem which is more of a functional flaw in base 10 than a real number theory issue

The context doesn't make a difference

In base 10 --> 1/3 is 0.333...

In base 12 --> 1/3 is 0.4

But they're both the same number.

Base 10 simply is not capable of displaying it in a concise format. We could say that this is a notation issue. No notation is perfect. Base 10 has some confusing implications

They're different numbers. Base 10 isn't perfect and can't do everything just right, so you end up with irrational numbers that go on forever, sometimes.

This seems to be conflating

0.333...3with0.333...One is infinitesimally close to 1/3, the other is a decimal representation of 1/3. Indeed, if1-0.999...resulted in anything other than 0, that would necessarily be a number with more significant digits than0.999...which would mean that the...failed to be an infinite repetition.Unfortunately not an ideal proof.

It makes certain assumptions:

Similarly, I could prove that the number which consists of infinite 9's to the left of the decimal separator is equal to -1:

And while this is true for 10-adic numbers, it is certainly not true for the real numbers.

While I agree that my proof is blunt, yours doesn't prove that .999... is equal to -1. With your assumption, the infinite 9's behave like they're finite, adding the 0 to the end, and you forgot to move the decimal point in the beginning of the number when you multiplied by 10.

x=0.999...999

10x=9.999...990 assuming infinite decimals behave like finite ones.

Now x - 10x = 0.999...999 - 9.999...990

-9x = -9.000...009

x = 1.000...001

Thus, adding or subtracting the infinitesimal makes no difference, meaning it behaves like 0.

Edit: Having written all this I realised that you probably meant the infinitely large number consisting of only 9's, but with infinity you can't really prove anything like this. You can't have one infinite number being 10 times larger than another. It's like assuming division by 0 is well defined.

0a=0b, thus

a=b, meaning of course your ...999 can equal -1.

Edit again: what my proof shows is that even if you assume that .000...001≠0, doing regular algebra makes it behave like 0 anyway. Your proof shows that you can't to regular maths with infinite numbers, which wasn't in question. Infinity exists, the infinitesimal does not.

Yes, but similar flaws exist for your proof.

The algebraic proof that 0.999... = 1 must first prove why you can assign 0.999... to x.

My "proof" abuses algebraic notation like this - you cannot assign infinity to a variable. After that, regular algebraic rules become meaningless.

The proper proof would use the definition that the value of a limit approaching another value is exactly that value. For any epsilon > 0, 0.999.. will be within the epsilon environment of 1 (= the interval 1 ± epsilon), therefore 0.999... is 1.

The explanation I've seen is that ... is notation for something that can be otherwise represented as sums of infinite series.

In the case of 0.999..., it can be shown to converge toward 1 with the convergence rule for geometric series.

If |r| < 1, then:

ar + ar² + ar³ + ... = ar / (1 - r)

Thus:

0.999... = 9(1/10) + 9(1/10)² + 9(1/10)³ + ...

= 9(1/10) / (1 - 1/10)

= (9/10) / (9/10)

= 1

Just for fun, let's try 0.424242...

0.424242... = 42(1/100) + 42(1/100)² + 42(1/100)³

= 42(1/100) / (1 - 1/100)

= (42/100) / (99/100)

= 42/99

= 0.424242...

So there you go, nothing gained from that other than seeing that 0.999... is distinct from other known patterns of repeating numbers after the decimal point.

X=.5555...

10x=5.5555...

Subtract x from both sides.

9x=5

X=1 .5555 must equal 1.

There it isn't. Because that math is bullshit.

x = 5/9 is not 9/9. 5/9 = .55555...

You're proving that 0.555... equals 5/9 (which it does), not that it equals 1 (which it doesn't).

It's absolutely not the same result as x = 0.999... as you claim.

?

Where did you get 9x=5 -> x=1

and 5/9 is 0.555... so it checks out.

Quick maffs

Lol what? How did you conclude that if

9x = 5thenx = 1? Surely you didn't pass algebra in high school, otherwise you could see that gettingxfrom9x = 5requires dividing both sides by 9, which yieldsx = 5/9, i.e.0.555... = 5/9sincex = 0.555....Also, you shouldn't just use uppercase

Xin place of lowercasexor vice versa. Case is usually significant for variable names.