I'm busy reading Foucault's recently translated Japan Lectures and I've come across perhaps the most substantial articulation of his critique of Marxism in the 'Methodology for a Knowledge of the World: How to Get Rid of Marxism' chapter, which captures a conversation with the Japanese New Left philosopher Ryūmei Yoshimoto. Foucault, from the vantage point of 1978, makes some pretty damning and insightful observations that resonate with the popular image of him as a quasi-anarchist figure (indeed, many anarchists were making these critiques long before the 1970s). Reading stuff like this it's no surprise the orthodox Marxist left are so anxious to disparage him as some kind of counterrevolutionary, liberal reformist or even CIA stooge.

Some excerpts:

“[W]hen it comes to political imagination, we have to acknowledge that we are living in a very impoverished world. When we look for where this poverty of imagination on the socio-political level in the 20th century comes from, it seems to me, after all, that Marxism plays an important part. That’s why I discuss Marxism. So you can see that the theme “How to get rid of Marxism”, which serves in some sense as a connecting thread for the question you have asked me, is also fundamental for my thinking. One thing is certain: that Marxism has contributed and continues to contribute to this impoverishment of the political imagination. This is our starting point.

“Marx is unquestionably a human being, a person who unerringly expressed certain things, in other words he is an undeniable being in terms of historical event… To transcend him would be as senseless as denying the Naval Battle of the Sea of Japan. The situation is totally different as far as Marxism is concerned. That’s because Marxism is the cause of the impoverishment, the desiccation of the political imagination that I was speaking about a moment ago. To really reflect on this, one must bear in mind that Marxism is nothing other than a mode of power, in an elementary sense. In other words, Marxism is a sum of power relations or a sum of mechanisms and dynamics of power. On this point we should analyze how Marxism functions in modern society. This is a necessary task, just as for past societies one analyzed the role played by scholastic philosophy or Confucianism. The difference being that in our case Marxism was not born of morals or a moral principle like scholastic philosophy or Confucianism. The case of Marxism is more complex, because it’s something that emerged, within rational thought, as a science. As for knowing what types of power relations a so-called “rational” society can assign to science, this cannot be reduced to the idea that science functions only as a sum of propositions taken for the truth. It is at the same time something intrinsically linked to a whole series of coercive propositions. Which is to say that Marxism as science—to the extent that it is a science of history, of the history of humanity—is a dynamic of coercive effects, concerning a certain truth. Its discourse is a prophetic science that diffuses a coercive force over a certain truth, not only in the direction of the past, but toward the future of humanity. In other words, what’s important is that historicity and the prophetic character function as coercive forces concerning truth.

“…Marxism as scientific discourse, Marxism as prophesy, Marxism as State philosophy or class ideology—are inevitably intrinsically linked to the whole set of power relations. If the problem of knowing whether or not to get rid of Marxism is raised, is it not at the level of the power dynamic formed by these aspects of Marxism? Marxism, viewed from this perspective, is today going to be called into question. The problem is less about telling ourselves that it is necessary to free ourselves from this type of Marxism than of throwing off the dynamic of power relations linked to a Marxism that performs those particular functions.

“…In defining the problem, an essential one for me, of how to move beyond Marxism, I have tried not to fall into the trap of traditional solutions. There are two traditional ways of confronting this problem. One is academic, the other is political. But whether it is from an academic or a political point of view, in France the problem unfolds broadly in the following way. Either one critiques the propositions of Marx himself, saying: “Marx puts forward such and such a proposition. It is true or not? Contradictory or not? Is it premonitory or not?” Or else one develops a critique of the following sort: “In what way does Marxism today betray what would have been reality for Marx?” I find both of these traditional critiques ineffective. In the final count they are points of view that are captive of what we can call the force of truth and its effects: what is true, and what is not true? In other words, the question “What is the true and authentic Marx?”, the kind of perspective that consists in wondering about the link between truth effects and the State philosophy that is Marxism, impoverishes our thought.

“…It seems to me that what we find in Marx’s work is, in some sense, a play between the formation of a prophesy and the definition of a target. The socialist discourse of the epoch was made up of two concepts, but was unable to distinguish them sufficiently. On the one hand, a historical consciousness, or the consciousness of historical necessity, or at any rate the idea that in the future one thing or another prophetically must come to pass. On the other hand, a discourse of struggle—a discourse, we might say, that stems from the theory of will—the goal of which is to identify a target to attack… But the two discourses—the consciousness of historical necessity, or the prophetic aspect, and the goal of struggle—were unable to play out to the end. This can apply to the long-term prophesies. For example, the notion that the State will disappear is erroneous. As for me, I don’t think that what is happening concretely in socialist countries points towards the realization of this prophesy. But as soon as the disappearance of the State is defined as an objective, Marx’s words take on unprecedented reality. Undeniably, we are witnessing a hypertrophy of power or an excess of power in socialist countries as in capitalist countries. And I think that the reality of these mechanisms of power, which are of gigantic complexity, justifies, from the strategic viewpoint of a struggle of resistance, the disappearance of the State as an objective.

“…the Party could always justify itself one way or another, as regards its activities, its decisions, and its role. Whatever the situation, the Party could invoke the theory of Marx as being the sole truth. Marx was the sole authority, and, because of this, it was considered that the activities of the Party had their rational basis in him. The multiple individual wills were consequently sucked up by the Party, and, in turn, the will of the Party disappeared behind the mask of a rational calculation consistent with theory passing for truth. Hence the different levels of will were bound to elude analysis.

“…Since it was believed that the Party alone was the authentic owner of the struggle, and since this Party was a hierarchical organization capable of rational decision, those zones imbued with a somber madness, namely the dark side of human activity or the obscurely desolate zones—in spite of being the unavoidable lot of every struggle— had trouble emerging into broad daylight. Probably only works that are not theoretical, works that are literary, or perhaps Nietzsche, have spoken about it. It doesn’t seem relevant here to insist on the difference between literature and philosophy, but what is certain is that on the level of theory we have not managed to do justice to this somber and solitary aspect of struggle. For that very reason we must increase awareness of this inadequate aspect of theory.

“We will have to tear down the idea that philosophy is the only normative thought. The voices of an incalculable number of speaking subjects must resonate, and we must allow an innumerable experience to speak. The speaking subject shouldn’t always be the same one. The normative words of philosophy should not be the only ones heard. We need to bring forth all sorts of experiences, lend our ear to aphasics, to the excluded, to the dying. Because we are on the outside; whereas they are the ones who confront the somber and solitary aspect of the struggles. I believe that the task of a practitioner of philosophy living in the West is to lend an ear to all these voices.”

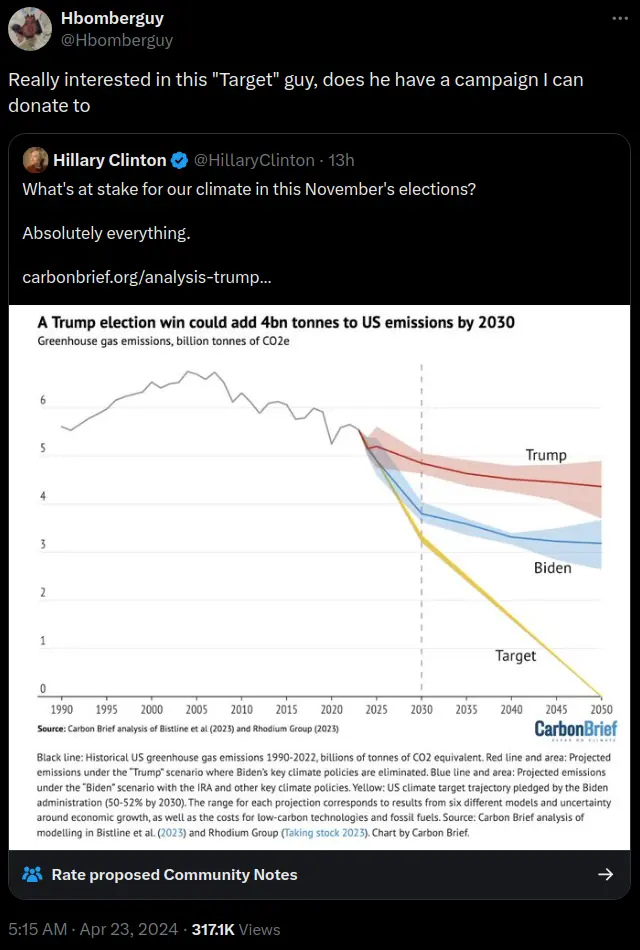

Presidents have power to legislate, it's called an executive order. Learn it in school. It's the most powerful presidency in the world. If they wanted to do it, they could. They haven't, so they don't want to. Simple as.